The Giant Sea Bass

The Giant Sea Bass Count

Written by Kristiana Rendón

The giant sea bass or black sea bass (Stereolepis gigas) are magnificent marine creatures because of their enormous size and long life span. They have many other interesting characteristics which you can learn more about in Megumi Itoh’s article posted below. Giant sea bass used to be an abundant species in the Southern California waters until the 1980s. Due to overly frequent commercial and sport fishing, they are considered a dying species, close to extinction. However, scientists and all divers can work together as a team to help improve the giant sea bass population and it is literally as easy as counting 1, 2, 3!

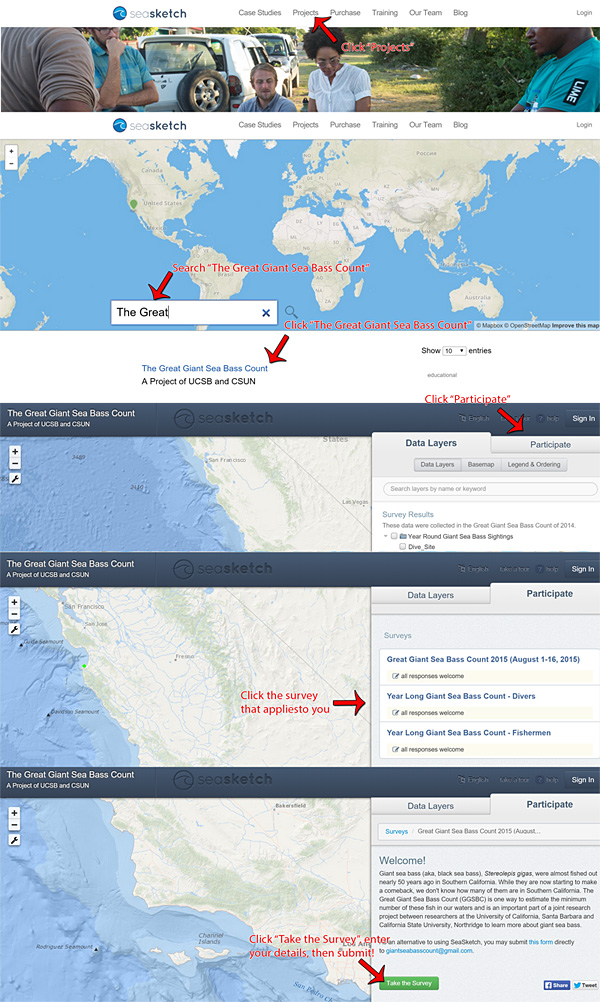

The team at SeaSketch has designed an intuitive system where divers can be citizen scientists simply be reporting the number of giant sea bass they saw or did not see. Any data that is reported to scientists is helpful even though none were spotted because they still provide information about their population. Additionally, having more reports from volunteer divers offer researchers more data to work with. You can send in your giant sea bass siting report in the following easy steps (below includes a picture guide as well).

Go to SeaSketch’s projects page (http://www.seasketch.org/projects/)

In the search bar, enter “The Great Giant Sea Bass Count”.

Click on the tab on the right that says “Participate”.

Click on whichever survey applies to you.

Click “Take the Survey”.

Enter the details from the site to the best of your abilities. If you can’t fill them all in, it’s ok. Remember some data are better than no data.

Double check your entry and click “Submit Reponses”. And you’re done! You just helped scientists get one step closer to saving the giant sea bass!

Now you can submit your giant sea bass count on the SeaSketch survey whenever you go out on your next dive. This time of year (August) is the giant sea bass’ mating season, so it’s the perfect opportunity to gather data. Let’s go out there and start counting!

Marine Life – Giant Sea Bass

Written by Megumi Itoh

Giant sea bass (Stereolepis gigas), also known as black sea bass and jewfish, are the largest fish we see in the California’s kelp forest. They are described as having bulky body with large head and mouth, low profile spiny dorsal (fore-dorsal) fin, taller soft dorsal (rear dorsal) fin, flat tail, and large dark spots over dark brown to gray body. However, you don’t really need to depend on this description to identify them. You will not mistake these massive fish for any other fish. They are rather ugly looking, but I would say they the most majestic fish we see in the local waters. They are simply massive and they move with such confident gentleness.

They are apex predator fish. When fully grown, their only predators are great white shark and people. According to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s Marine Sportfish Identification, they can grow to be over 7 feet long and weigh over 500 pounds. They range from Humboldt Bay, California to Baja California, Mexico, and Gulf of California. They aggregate mainly south of Point Conception in the 35 to 130 feet range, in the kelp beds with rocky bottoms near drop-offs.

Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach, California has three giant sea bass in captivity (they have a special permit from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife). The two larger fish are male and female estimated to be around 30 years old, and the third is presumed to be a young male based on its behavior pattern. They live to be at least 50 years old, and they sexually mature in 10 to 13 years. The oldest known specimen was 72 years old. Their mating season is from June to September. This is when the divers most often see them in large aggregation.

I have learned a few surprising facts about this fish when I did my research for this article. The juveniles look drastically different from the adults and are often mistaken for other fish species. The juvenile’s body shape is more perch-like, and the color is sandy red to orange with white spots and irregular dark patches. They are found in the kelp beds and sandy bottoms at a shallower depth than the adults. The other surprising fact is that the adults have the ability to change the appearance of the dark spots on their body at will. It is believed that they use this ability to communicate stress and other signals to other giant sea bass in the area. This explains why sometimes the spots look distinctive and at other times they are barely visible.

These fish were once abundant in California, but they were hunted to near extinction. According to the 2008 Status of Fisheries Report by the Department of Fish and Wildlife, commercial fishing of giant sea bass began in 1870 in southern California, peaking in 1932. Recreational fishing began in 1895, and peaked in California in 1964 and in Mexico in 1973. Both commercial and recreational fishing were banned in 1981, but a loophole in the law allowed for their continued hunting. Commercial gill net and trammel net fisheries were allowed to take two fish per trip, and the fish could also be caught in the Mexican waters and brought into California with the limit of 1000 pounds per trip and 3000 pounds per year. The law was amended in 1988 to allow only one incidental catch to be brought into California. Unfortunately, both commercial and recreational fishing of these majestic fish are still legal in Mexico.

The number of their sightings by divers has been increasing in recent years, but there is no scientific evidence of their current population status. I have only seen them a handful of times over the last seven years (and I dive primarily in southern California). The closest I have ever gotten to one was at San Clemente Island in 2009. I was swimming through a kelp bed and apparently a giant sea bass was swimming along in the same direction on the other side. We both turned at the end of the kelp bed and came face to face with each other. It took me a few seconds to realize what I was looking at. I was close enough to see the white thread-like parasites on its nose. When my brain finally started to work again and remembered I had a camera with me, the fish started to swim away. I probably moved too suddenly and startled it into motion. I got a few parting butt-shots before it disappeared. Since then I have seen a small school of them at San Clemente and Anacapa Islands. Seeing one is amazing, but seeing a school of them swimming around you is breathtaking. I hope their number will continue to increase so these encounters will be more common.

One Diver Pursuing Dreams Through Skill and Determination

It all started one day when I answered a casting call for female scuba divers that Ocean Safari had sent me. I wasn’t expecting to get any reply from the casting director because of my one past experience with acting auditions (I was nine years old when a director simply looked at me and said that my nose was, “Too flat for film”).

So, you could imagine just how excited my little nineteen year-old self got when the casting director replied, “The director and agency would both like to meet you at callbacks."

Callbacks took place at the pool of Malibu’s Pacific Palisades High School. As I entered the pool’s gates and saw the gorgeous, fit ladies that I would be auditioning with, I pretty much accepted a rejection. I reckoned there was no way this less endowed, little Asian girl could compete with the bombshells of Hollywood.

So once again, you could probably imagine just how loud I screamed when the casting director called me a few hours later saying, “You got the part.”

I later asked the director and agency members why they had chosen me, and their answer was simple, “Skill.” I was able to hold my breath and swim for fifty-two seconds at auditions, and paddleboard comfortably. I thought of Ocean Safari then, and all the training that Gabe, Luis, Stu, and the guys, Thomas & Andy, had drilled into me. And I also thought about Tyler at Cove Paddle Fitness, and how determined he was in making sure I had the right stroke technique.

I giggled to myself then because it took me nearly twenty years (of which seven were spent in the infamous “teen” years) to truly realize that: it’s not about what you look like, it’s about what you can do. Thank you, Sean Meehan, Jon Reil, and Andy Schneider for helping me see this.

Though these skills seem pretty simple, they were absolutely exhausting to do continuously for hours and hours, without breaks or food (I couldn’t eat, or else I’d vomit). In fact, at one point during filming, I was so pale-faced and exhausted that I simply could no longer care about how I looked in the commercial (which I now of course regret haha).

All in all, there is no way I could have completed the filming of this commercial without the training that Ocean Safari has given me, and the amazing crew who helped keep me and my spirit alive during filming. Even though you only get to see my beautiful self in this commercial (hehe), it is the product of the hard work of hundreds across our nation. Shout out to my main stuntmen James Mitchell-Clyde, Kris Jeffrey, Mike Brady, and Kevin Mills (who is also an OSDT diver by the way!), and the talented cinematographer Chris Lum. It was a pleasure to work with all of you at JAMRS, Mullen, Arts & Sciences, Outcast International, and our DoD. I would do it all again in a heartbeat, and better yet, I would happily do it all for free!

But above all, thank you Ocean Safari for the chance of a lifetime, and all the dives, pool sessions, training, and love that you’ve given our OSDT community and me. I love you all so very much, and will dive with you for the rest of my days!

Written by Brittany Rain Tran

Current At Santa Rosa Island 4/18/15

Diving in the kelp forest at Santa Cruz Island.

“The current is pretty strong, but you should be able to make it,” James, a Peace crew deckhand, reported back after jumping into the water at our first dive site. We were outside Nunya Reef at Santa Rosa Island.

Thomas explained that we would make our giant stride off the bow, stepping as close to the anchor line as possible, and swim for the line. If we couldn’t immediately grab hold, we would be swept toward the back of the boat where we would have to abort the dive and board the swim step. I had no practice swimming in current, but I was determined to get to that anchor line.

Once I dropped into the water, I felt the current rip at me immediately. Visibility was low but I could see the anchor line and I kicked for it. Still, it remained just out of my reach and I was exerting too much energy, burning too much air. The idea of aborting the dive was crushing, I was so close. In one last-ditch effort, I kicked harder and threw my arms out in front of me. Megumi, one of my assistant instructors, was hanging on the line and my hands grazed her fin. I grabbed hold. I was worried that I’d yank her right off the line, but hopeful that she might be able to pull me to it.

She turned her head and grabbed my arm, guiding me as I continued to kick and finally my fingers wrapped around the rope. Once I was secured on the line I laughed into my regulator. It was so fun to hang on and let the current blow my body out behind me like a windsock. As I relaxed, my breathing slowed, and I descended the line after Megumi.

Down at the bottom, the current was calmer and we had a chance to explore the reef. The visibility was about fifteen feet. Once I let go of the anchor line I saw that my entire group had made it! We were seventy feet deep and soon it was time to ascend back up the line. I was a lot more comfortable with the pull of the current on my way up, enjoying the power of it, it was an exciting thing to behold.

There is nothing like a hot meal to recharge a group of divers. Courtesy of Peace crew chef Steve, the Ocean Safari Dive Team enjoyed a fresh breakfast as we made our way to Santa Cruz Island for our next dive.

I plunged into the water after Megumi and met up with my buddy and the rest of my group at fifteen feet. At a depth of fifty feet, we began exploring the underwater rock formations. I watched Thomas shine his light into one of the crevices, but I couldn’t see what he was looking at. He grabbed my arm and pulled me closer, and I followed the direction of his light as I swam inside. I thought that he might be showing me a lobster or eel, but when I got in closer I came face to face with a beautiful horn shark (Heterodontus francisci). I’d never seen a shark outside of an aquarium before, it was enthralling.

Back on the boat once again, we enjoyed some of the luxuries only found on the Peace. Divers warm up in-between dives by pouring hot water from the boats jacuzzi down their wetsuits! Our captain dropped anchor at Bowen Point, on Santa Cruz island for our third dive. I kept my buddy close and followed Thomas, but soon we realized that our group was missing two divers. We searched for them briefly underwater before ascending to the surface. My buddy and I took a compass heading before descending and heading back to the boat.

Despite getting separated underwater, the missing divers navigated their way back and we all rendezvoused on the boat before our captain pulled up the anchor a third time and moved us to Pink Ribbon Boilers, our last dive site of the day, on Santa Cruz island. Before jumping off the boat, my buddy and I took a compass heading and then performed our direct descent. We explored through the kelp and saw California Garibaldi (Hypsypops rubicundus), urchins (Centrostephanus coronatus, Strongylocentrotus purpuratus, Strongylocentrotus franciscanus), sea cucumber (Parastichopus californicus), sea hares (Aplysia californica), schools of blacksmith (Chromis punctipinnis), and sand dollars (Echinarachnius parma).

As part of Ocean Safari’s NAUI Advanced Open Water Certification course, my instructors guided me through challenging conditions and helped me to progress my level of skill and competence under water. Back on board I logged my dives and relaxed in the hot tub as the Peace made its way back to the harbor, taking the Ocean Safari Dive Team back home.

Written by Sara Hall